|

Register or Log In To remove these advertisements. |

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

Thread Tools | Display Modes |

|

|

#1 |

|

Registered User

Join Date: Jan 2013

Location: Leonardtown, MD

Posts: 1,648

|

A couple years ago I helped with a metalshaping demo in Berryville VA, where the focus was to be on hand tools so that anyone could duplicate the results inexpensively. I didn't get as many pictures of the event as I normally would with my typical tech threads done from my shop, (too many hammers in my hands) so this will be supplemented with some diagrams to make a good tech thread.

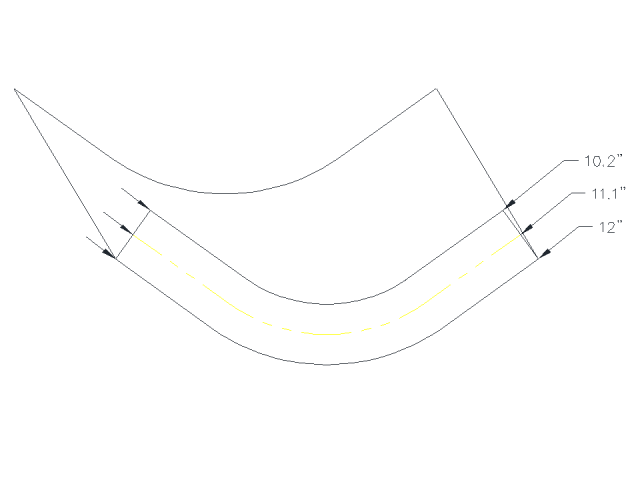

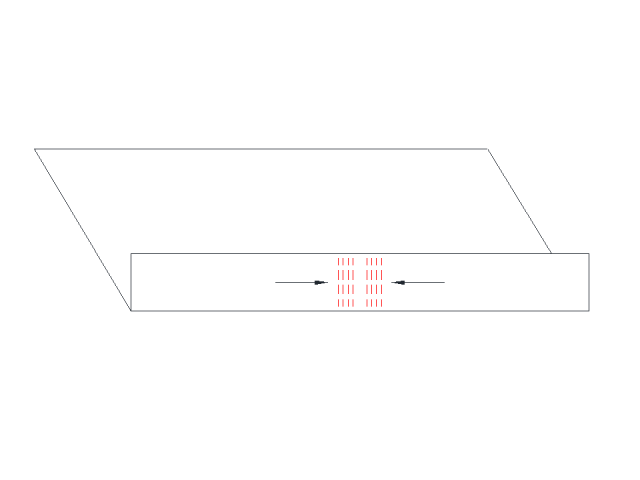

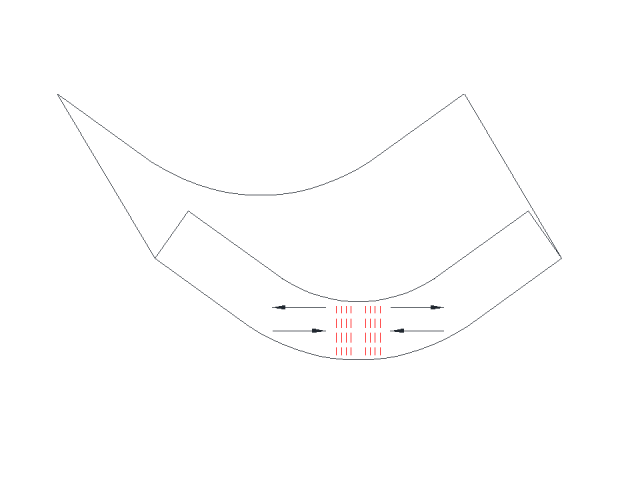

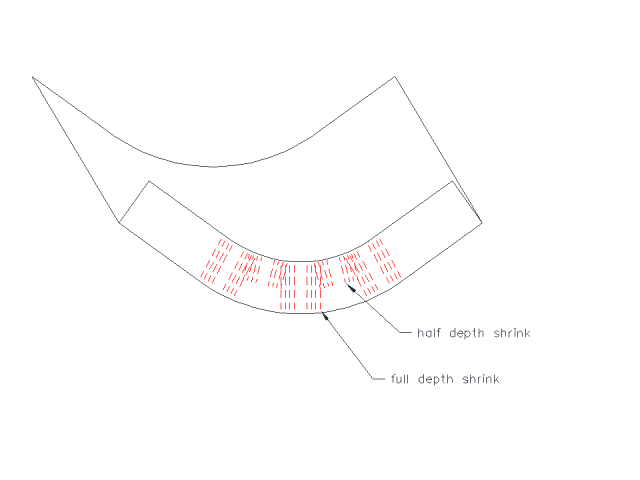

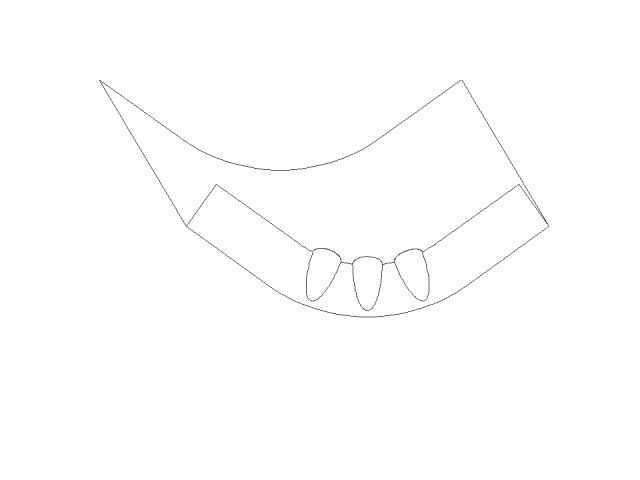

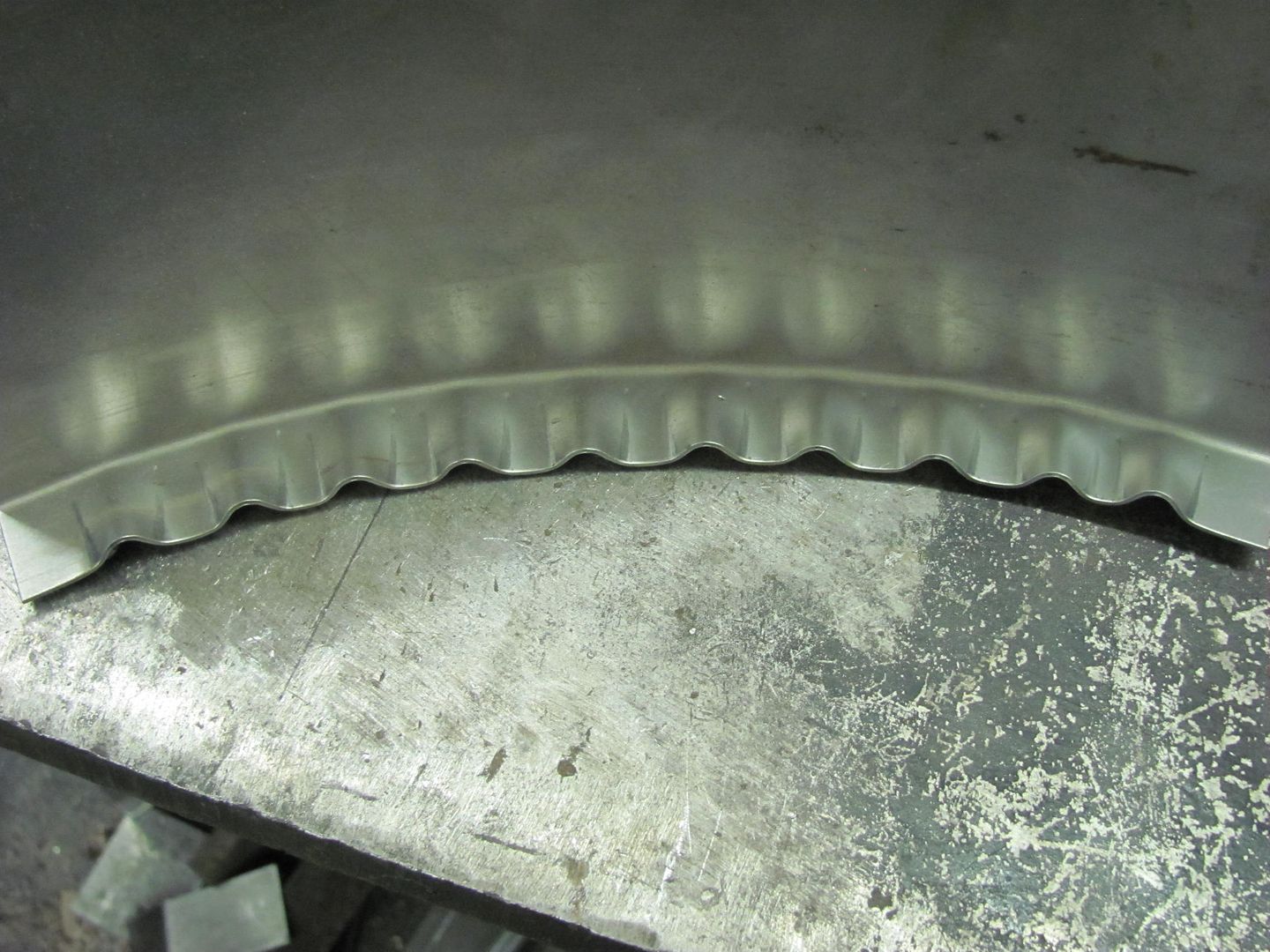

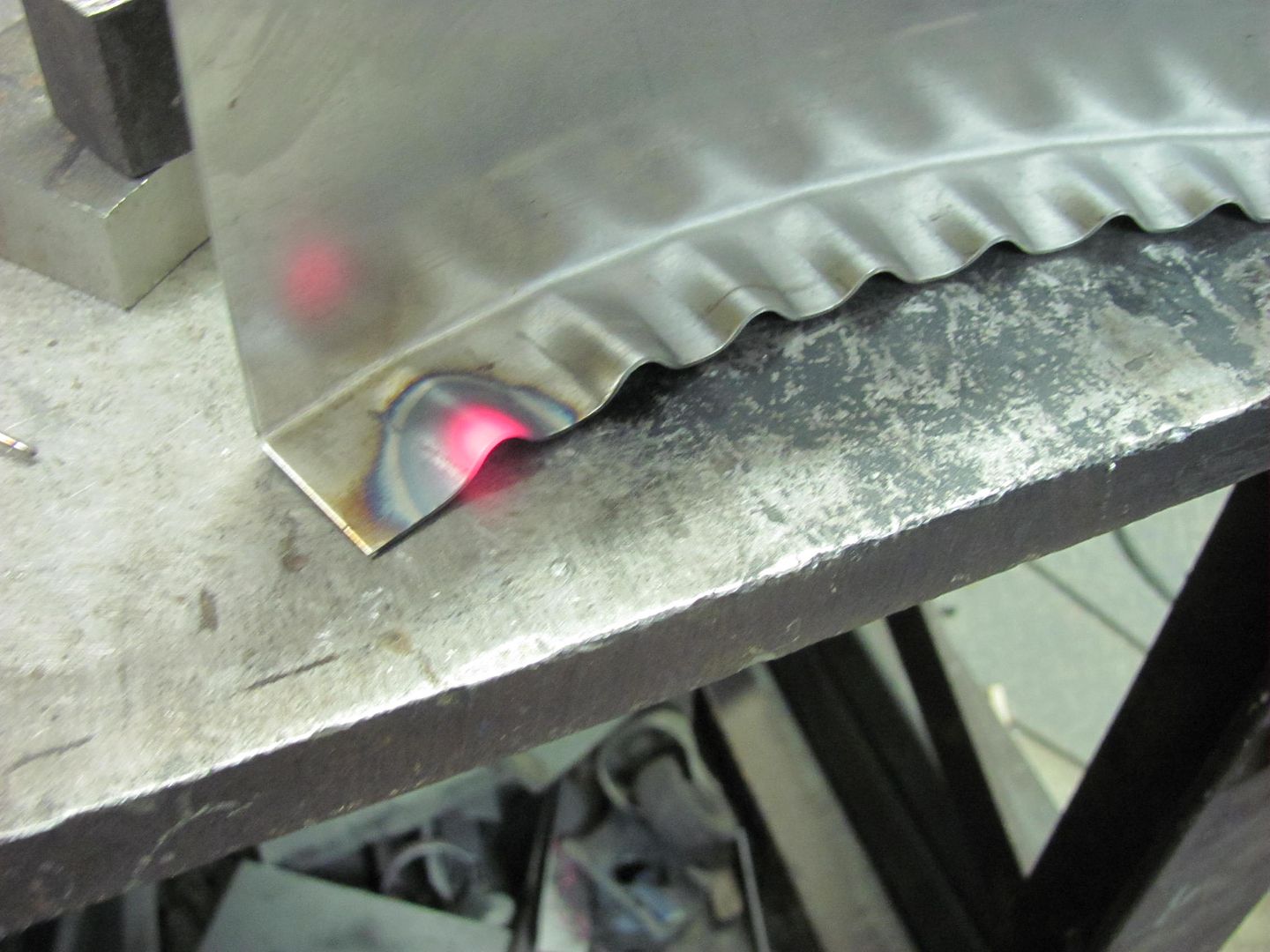

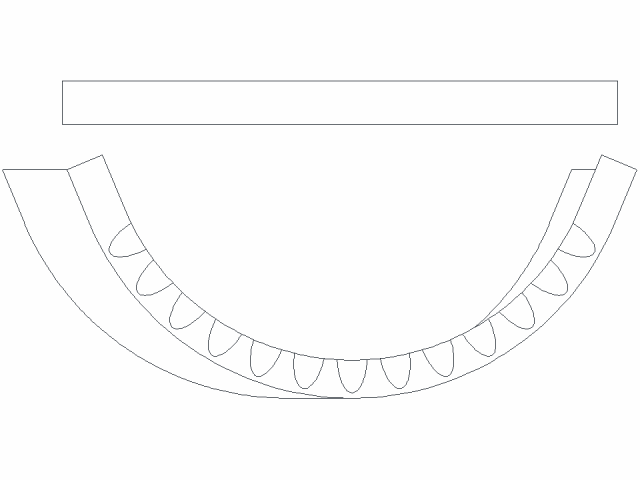

Your typical Lancaster type shrinker stretchers are in the neighborhood of 150+ and as we are trying to show these skills using "cheap" tools, this thread will discuss tuck shrinking. For the demo, I started with a 12" long panel with a 1-1/2" wide flange bent on the long edge. Then discussed some of the issues faced when shrinking a flange. For demonstration purposes, in the following pictorial we have a 12" long panel with a 1-1/2" wide flange.  If we were to look at the same panel with a radius, formed by shrinking the flange, we would note dimensions similar to as follows:  ....where the 90 degree bend at the flange still retains its 12" length, the centerline of the flange in this case is shortened by almost an inch, and the outer edge of the flange shortened by almost another inch. In working with the Lancaster/Eastwood style shrinker-stretcher machines, it is important to note that they are a linear device, the movement they introduce into the metal is in a straight line.  So that once a radius starts to form, and with the shrinking device still moving in a linear fashion, the outer edge of the flange will be put into tension as the centerline shrinks. Anyone who has used these devices will have seen this as the machine starts to lose its effectiveness.  To counter this effect, we need to shrink the outer edge of the flange more than the inner. By simply alternating the depth of the shrink as shown, you can provide more shrink to the outer edge and the device will become more effective.  Another method of shrinking is with the use of tucks. Looking at their shape, the tuck has a wider "gather" at the edge of the flange as compared to the inside bend of the flange, so this eliminates some of the tension issues seen in the mechanical shrinker.  Where the demo was to concentrate on using only hand tools so that the participants could readily duplicate the results without the need for a major purchase, we did find the use of the Shrinker a good comparison, and by chance the tuck shrinking did prove to be faster and more effective for the wider flange we were using. For the tuck shrinking, one can use tucking forks, rounded jaw pliers (by design or modification) or special designed devices. As an example, here is a set of tucking forks I made out of some scrap metal and 5/8 bolts turned down.  And a pair made from needle nose pliers..  Probably the biggest challenge with using either of the above tools is producing consistent tucks. To produce a flowing, consistent radius, we should start with consistent tucks, both in size and the spacing between them. I decided to make a pair of tucking pliers out of Vice Grips, as the jaw adjustment on them would prove to give repeatable sized tucks. We'll start off by finding a pair of vise grips suitable for the job, which in this case means the jaw serrations are starting to wear and round off and won't grip much of anything else. Finish what has started by removing the serrations to produce a nice flat jaw on the bottom, and cut the top one off at about 30 degrees from its original position.  I had some extra long shouldered 3/8 bolts, perfect round stock for the job. Three of them were cut off to 1-1/2" length.  Here's my economy model lathe made by Dewalt...  To set the spacing for the "fingers" the first is clamped in the vise grip jaw, centered.  The outer is placed next to it and then welded down the outside, center finger removed, and then welded down inside. Here we should leave a slight gap of your sheet metal thickness to prevent any binding, which will allow a deeper tuck.    Repeat for opposite side, then weld center finger.   Note in the above picture the 30 degree cut of the upper jaw positions the center finger at an angle compared to the bottom fingers. It is this angle that will help to form the tuck's shape. Of course I took my favorite anvil along to the meet, here clamped in the vise..  Again our object in this case is consistency, so equally spaced marks are placed on the flange, identical tucks made at each mark, and you can see the consistent radius along the panel.    I use a O/A torch to heat the tucks prior to hammering them flat. Others prefer to not use heat, and can capture the tuck and flatten it very effectively without it. I am still working on this proficiency, so in the meantime, I use heat. We're looking for something like this, prior to hammering.  Here OJ assists with torch duties...  Another point to mention is that the hammering action tends to also spread the tuck back apart if not captured effectively. Where the picture above doesn't show it well, a good means of overcoming this would be to clamp a strap of metal across the ends of the newly formed radius prior to hammering, similar to this:  Then the hammering force will be more effective in flattening the tuck back into itself.

__________________

Robert |

|

|

|

| Bookmarks |

|

|